TV Shows and videos:

HGTV: That's Clever

Brighthouse: The Art of the Craft (Part 1 of 3)

The Art of the Craft (Part 2 of 3)

The Art of the Craft (Part 3 of 3)

Articles about Bobby Michelson

Woodworkers Journal | Alabama Artists Fellowship Recipients 2000-2002 | Woodshop News |

Bobby Michelson: Throwing the Ball Higher

from Woodworkers Journal eZine Sep 24 - Oct 8, 2002 edition

By Lee Gilchrist

Conservative contemporary is about the only term Bobby Michelson will accept to describe his unique style of furniture. A keen observer, however, might also note how his graceful furniture maintains a careful balance between art and function. Delicate curves predominate and masterful joining bring the whole piece together. His work has been displayed at art shows across the country, and he recently received a special recognition from his home state by winning a 2001 Individual Artists Fellowship in Craft award (worth $5,000!) from the Alabama State Council on the Arts.

Bobby's success started 20 years ago, when he first decided to do something he really enjoyed. It took a few years, however, to reach that decision.

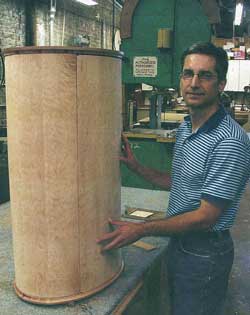

Birdseye Curio Cabinet

"I got my first taste of woodworking in junior high shop, but my

dad was a dentist and we didn't have any tools, so that really didn't

go anywhere. In fact, I started in pre-med and pre-dental at the University

of Alabama . I was always good in science and thought about following

in my father's footsteps, but I didn't have the grades to get into professional

school. Since I enjoyed the psychology of marketing, I switched to business

and marketing. Then I discovered during my senior year, that all the entry

level jobs would be sales-related … and a salesman I'm not."

So Bobby ended up with a marketing degree and unsure what to do next. A retail job didn't last long, and with a pretty limited background, he found a job with a high-end cabinet shop that was just starting out. Gaps between jobs, however, soon resulted in his being laid off. Then he worked off and on for the next four years for another woodworker who specialized in Californian Roundover (popular in the late 1970's, this furniture was characterized by rounded corners and soft lines). After a subsequent tenure with another high-end shop ended after only a year, Bobby's frustration led him to go into business for himself.

"When I decided to go into business, I had a hand drill, a sander, and few hand tools. I had saved up a little money and decided it was time to find a building and equipment." Bobby recalled. "So I started going to auctions looking for equipment. I didn't feel like I needed everything, but at least a full complement of a joiner, table saw, planer, radial arm saw. First thing I built was outfeed table for the table saw. Then my first paying project was a tiny cabinet job. That afforded me the money to build a simple assembly table. After that first month of buying a few tools and equipment, I was pretty much living on a shoestring."

Fan bed

Aside from what he learned at the various shops, Bobby improved his skills

by reading magazines (Fine Woodworking was a favorite), went to a few

seminars, and basically by trying and doing learned to enjoy the processes

and challenges of higher-end furniture. It was a struggle at first between

making a living and creating the kind of pieces he wanted to make.

"When I started out going to shows, I'd have some show pieces, but I'd also have some simple sellable pieces," Bobby recalled. "I soon realized that this was a "show" and I needed to show off. I decided to try to sell only at the level of the work I wanted to make. Unfortunately, a lot of people beat their heads against the wall trying to compete with the commercial furniture makers' prices. You just can't survive at that level … in this day of mass merchandisers there'll always be somebody cheaper. So, the only way to make any money is to throw the ball high! Part of my product identity is always trying to raise my level as a craftsman."

"I knew a few people and picked up a few commissions that paid the bills, but when I got caught up I'd do the speculative pieces. Then I marketed them pretty much through art shows, sold some, and slowly over the years built up a clientele. And here we are 18 or 19 years later," he laughed.

Nature or Nurture Bench

Most of Bobby's influences have been relatively subliminal. Though he

never studied Frank Lloyd Wright, his parents had (still have) a mass-produced

dining and living room set designed by Wright. His piece, Frank's Coffee

Table, pays subtle tribute to the Twentieth Century master architect.

Though he didn't know his name, he discovered at his first Furniture Society

conference that the work of Michael Fortune had made a big early impression

on him. As had the distinctive shell desk of Jere Osgood. He admits that

his respect for the wood -- he sometimes try to determine what the wood

wants to be -- sounds Krenovian. And with his recent Nature or Nurture

series, most people see the influence of George Nakashima with his use

of natural slab edges.

"A lot of times when I see pieces that I like, I wished I hadn't seen them because … gosh, I can't do that now," he declares.

He likes doing commission work because starting is the hardest part of what he does. And he encourages his clients to bring in their ideas … even a stack of pictures that they like. Then he can begin feeding off their ideas. The speculative pieces he does are often determined by what he's recently sold during a show.

"I need two tall pieces for the corners of my display, some sort of coffee table for the middle, and some other pieces," Bobby explains. "So, when a piece sells, its position in his show display often determines part of the design."

To create his own designs, he sometimes just sits down in the office and starts sketching to get an overall feel. He then goes into the shop, gets out a piece of plywood and starts laying it out in a full scale drawing. This allows him to look at the curves from long angles and get comfortable with the shape. The next step is to start drawing the curves on the wood … adjusting the proportions to the size of the wood.

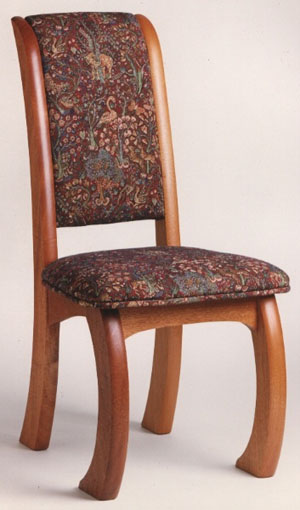

Fast Chair

The Nature or Nurture series is a result of that process … plus

having access to a supply of hardwood slabs.

"I've been getting the slabs from a gentlemen who lives near Lynchburg , Tennessee . He's a retired woodworker and is selling off his stored wood. Though most of his wood was squared off, near the edges of the barns and shed I found these natural edge slabs. After I'd done a few pieces, I came back with a couple, one to show him and one to give to him in appreciation. But, being pretty traditional, he just didn't get it."

That's an attitude that Bobby went up against for his first 14 years in the business. Until one day he had what he calls a transition point and decided that, if he was going to do this, he had to throw the ball high again and started applying at some of the bigger, nationally renowned art shows. It's a transition that paid off, and this year he's done shows in Chicago , Philadelphia , and Ohio .

"They just seem to 'get it' better up there," he noted. "Though there's still a lot of people who don't appreciate the amount of time involved. And when I ask some folks about the color of wood they want, they say it doesn't matter because they want it stained dark. They just don't realize wood comes in different colors. I've got a friend who had a customer come in who got all perturbed because he wouldn't tell him where to get a can of patina."

He loves the interaction at the shows, but finds there's only so much he can say. That's where his website comes in. He thinks of it as a brochure that, though it doesn't bring him any direct sales, provides a way to tout his work and perhaps give his customers the confidence to write a big check for a commission. He also enjoys the loyal clientele he's developed over the years, particularly when he gets to go back and see something he's sold them a while back.

"It's gratifying to see

my pieces fit into both contemporary and traditional settings," Bobby

declared. "And it's a lot of fun to come back and see some of my

older pieces, particularly the ones in cherry that develop a rich patina,

and think, my God, they're even prettier now than they were."

Bobby Michelson 2001 Fellowship in Crafts

from Alabama Artists Fellowship Recipients 2000-2002

Alabama

State Council on the Arts

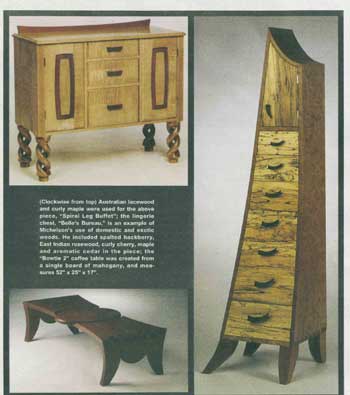

"Curly cherry, ash, walnut,

monkey pod, mock orange, spalted hackberry, Austrailian lacewood, wenge,

padouk", says Bobby Michelson, naming some of the fascinating materials

he uses in his hand-built furniture. To a woodworker, unusual woods have

the same value as precious gemstones.

"You can do a great design in a nice wood and get a beautiful piece of

furniture, but if you do the same design in a fancy or exotic wood, it

makes all the difference in the world," Bobby says. "exotic woods make

a piece stand out, make it really special."

Bobby's first real memory of being affected by wood comes from watching

the funeral of President John F. Kennedy on television and "being struck

by the beauty of the mahogany casket glowing in the sunlight." He was

five years old at the time. It was in shop class several years later,

in junior high school, that Bobby "fell in love with wood." After graduation

from the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa with a business/marketing

degree, he apprenticed with several Birmingham woodworkers, then, at age

25, he established his own studio, Ramwood Furniture (his initials plus

the word "wood"), in the location where he remains today.

Bobby has honed his craft through seminars, workshops and hands-on experience.

"When I took a seminar on hand-carving, I realized that you can watch

all the videos and read all the instructions you want to, but nothing

takes the place of picking up a chisel and doing it yourself."

He indicates a magnificent five-panel folding screen and says it took

him close to 80 hours to carve its exquisitely simple vine motif. The

intricate double-helix legs that are a signature of his are primarily

hand-carved. He likes to point out the pieces he's made with "no electricity"--only

hand tools were used.

Bobby looks for colors and textures of wood that complement each other;

one of his specialties is exposed joinery. Two different woods with high

color contrast accentuate such details. "My forte is making solid wood

pieces, using traditional joinery, in conservative contemporary styles,"

he says. He applies that to armoires, bookcases, desks, chairs, credenzas,

coffee tables, jewelry chests, side tables, dining tables, and chests

of drawers--he has made them all.

Text by Mary Elizabeth Johnson Huff, Montgomery

Alabama State Council on the Arts

201 Monroe Street, Suite 110

Montgomery, Alabama 36130-1800

334-242-4076

Issue Date: January 2005

Brian Caldwell

Why work with standard woods when exotics are more fun and attract customers, asks this Alabama woodworker

At

first glance Bobby Michelson, a studio furniture maker in Birmingham,

Ala., appears to be a fish out of water. His contemporary designs don't

reflect the majority of furniture found in Birmingham or the state of

Alabama. However, after 20 years of operating a one-man shop in Birmingham,

Michelson has found a national market for his furniture.

At

first glance Bobby Michelson, a studio furniture maker in Birmingham,

Ala., appears to be a fish out of water. His contemporary designs don't

reflect the majority of furniture found in Birmingham or the state of

Alabama. However, after 20 years of operating a one-man shop in Birmingham,

Michelson has found a national market for his furniture.

"Around here there are some expensive neighborhoods where there's a lot of money," said Michelson. "I guess the attitude is to go for The Look. They'll buy expensive cars, they'll wear expensive clothes, expensive jewelry, but they don't buy expensive furniture."

And that's why you are more

likely to see Michelson at furniture and art shows in Philadelphia; Orlando,

Fla.; Peninsula, Ohio; Denver; and St.

Petersburg, Fla., instead of the smaller art shows in central Alabama

that he frequented in his early years as a furniture maker.

Sweeping floors to shop owner

Michelson graduated from the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, with a marketing degree. Although he had taken shop since junior high school, a career as a furniture maker was not foremost in his mind when he entered the working world. Fresh out of college he took a job in the retail sector and struggled for nine months. He quickly realized that sales was not his bag and decided to pursue an area he enjoyed as a youngster - woodworking.

"I made some contacts and got my first job as the installer's helper and floor sweeper in a high-end cabinet shop. Then I apprenticed with a guy that made all solid wood furniture; it was very nice, but very simple design. His idea was to make custom furniture for the average guy. Therefore, if he couldn't get a table in and out of the shop in a couple of days, he didn't want to fool with it. My one fringe benefit was using the shop after hours."

For

nearly five years he bounced around Alabama cabinet and furniture shops,

gaining knowledge and developing confidence. Then he became so frustrated

with the way one owner ran his shop, Michelson made the bold decision

to open his own custom furniture business.

For

nearly five years he bounced around Alabama cabinet and furniture shops,

gaining knowledge and developing confidence. Then he became so frustrated

with the way one owner ran his shop, Michelson made the bold decision

to open his own custom furniture business.

"I was hooked from the beginning. It is the kind of thing where the more things you do, the more successes you have, the more excited you get about it. And then there's the attitude that I'm producing something. At the end of the day I can see what I produced, created, and I get a lot of pleasure from that."

He went shopping for a building

and found a 2,400-sq.-ft. shop with 14'

ceilings in Birmingham. The place had numerous leaks, but was roomy and

had the ultimate in advertising - a billboard on the roof. He was able

to purchase his new workplace at a reasonable price and proceeded to shop

for tools and machinery. He opened Ramwood Furniture in 1984. Ramwood

is derived from the first initials of his full name: Robert A. Michelson.

It's the curves

Through his 20 years of furniture making, Michelson's contemporary designs have evolved from fairly simple to rather technical, at times daring, and usually with plenty of curves.

"To me it seems like a

natural progression - the more you do the farther you go with things,"

he said. "It's kind of a stepping stone. Even in my best pieces,

I can look and say maybe I could have done this a little different.

With your own acceptance, it's almost like permission to go a little further.

So the designs and look [do] evolve and you kind of develop your own design

language. If you look at my portfolio, I feel like I show a lot of versatility,

but at the same time, you'll see similar curves, relating themes and that's

part of the design evolution."

In the early days he marketed locally and hit the art show circuit. He exhibited at art shows for 14 years before deciding to pursue a national clientele.

"My stuff was unique but at an art show unique is not good. It's good to win awards and to have compliments, but if they didn't come to the show expecting to see something, there's a good chance they're not going to buy it. I'd rather go to a show where I do have some competition; that means people are coming expecting to see furniture, and therefore might be more willing to purchase."

In 1998 Michelson changed his selling philosophy and entered the world of national furniture shows. From St. Petersburg, Fla., to Philadelphia, Orlando to Denver, Michelson's furniture went before a new buying public - one with a very discerning eye.

"I decided if I'm going to go for it, I'm going to go for the bigger shows with more potential," he said.

Michelson is a regular exhibitor at the Philadelphia Furniture and Furnishings Show each spring.

"It's been a pretty good show for me. I've been there three or four years now. I like that show because the people that come are wearing nice shoes and carry a tape measure. So they can afford it and they're looking for furniture. The first year I went, I was a little apprehensive. I kind of expected to be intimidated. The quality of the work is fantastic overall.

"At a lot of these shows, the people buying higher-end work, they're buying the artist's name. You can go anywhere and buy a table. Part of my motivation in doing some of the better shows, hopefully winning a few awards along the way, is to raise my stock as an artist, to raise the value in the pieces. There's always someone who can do it cheaper. So I'm trying to do something a little different, not a lot different, because my look is still kind of an elegant, contemporary yet classic look."

Function first

"Function is of utmost importance," Michelson said about his furniture. "I like, when possible, to put a little hidden drawer in or whatever, to be efficient with space. There's usually a reason for things. For me, some of the art furniture chairs that you can't sit in, I don't get it. I'm making furniture to go into people's homes. I would love to have some in museum collections, but the chairs you can't sit in, those go into museums. There aren't too many people who buy those for their homes.

"To me, it's a balance between art and design but my attitude is that it has to be functional. A chair - first it has to be comfortable, but it also has to be strong to last. I've seen some wild designs with legs where some guy, a little above average-size, is going to rock back and the thing is going to snap. I can't do that."

Michelson's custom designs are derived from ideas that he visualizes, which he then follows up with conceptual drawings. There aren't any CAD programs in his shop. The most sophisticated design work he employs is an occasional plywood mock-up.

"My drawing abilities are not what my woodworking abilities are. In a way, it makes it a bit more difficult because drawing is a great tool to sell with, and I always have to have a sort of disclaimer. I can give you a feel with the drawing, but a draftsman didn't do it.

"At the shows, you can see the quality, see the finish, and therefore get the confidence that I have the ability. For a customer, I'll try to have a pretty complete design idea as we complete the contract."

Over the years Michelson has developed his Nature or Nurture series of furniture. Many of the pieces are slabs with natural edges, similar to work made famous by George Nakashima.

Shop talk

Michelson doesn't advertise much; he has a slight presence in the Yellow Pages. Word of mouth and exhibiting at national shows remain his best advertising, along with the Birmingham billboard.

"I have people all the time stop in and say they've seen my billboard lots of times, and they've just wondered what goes on in here. A lot of times, curious people are potential clients."

His spacious shop contains an array of machines, which have been acquired from a variety of places, including U.S. Steel in Birmingham, and even a Newman 12" jointer from an aircraft carrier. A 1926 Oliver 288 band saw dwarfs all the machines in the shop, which include a Rockwell 14" band saw, Powermatic 66 sliding table saw, Onsrud inverted router, Crouch edgesander, imported 20" planer, and a homemade downdraft table and dust collection system.

"I used to try to keep a part-time apprentice," Michelson said. "The past years, when the economy decreased, I let my last one go and I've enjoyed working alone since. I would tend to find myself being their support crew instead of them being mine. When I have something involved or detailed to do, if there's somebody else in here, I'm easily distracted."

Many of Michelson's contemporary pieces are built with exotic woods, a factor that the builder feels can contribute to the value of a piece.

"My attitude is you can do a great design in a nice wood and it's a great piece of furniture. But you do the same design on a wood that is really striking or unique - and especially at a show - that's the piece that draws you in. If you use a curly figure or bird's-eye or something like that, that 's the piece that people walk to. You spend a little more on materials and basically the same labor and you end up with a much more marketable piece, a much more unique piece. I do this day in and day out so wood like oak, which is a perfectly fine wood, is a little common. It's more exciting to use something that's not common."

The next 20 years

Michelson seems content with his work and where he stands in the studio furniture-making community. His designs will continue to evolve due to his desire to keep pushing the edge a bit further.

"When I go to a show and get a commission, it's an opportunity to do something else, something different. I enjoy what I'm doing; I enjoy making one-of-a-kind furniture. I like the challenge of craftsmanship, the physical part of the work. So I'd like to keep doing what I'm doing.

"I think for any artist,

we all have egos and that's a lot of the reason you do what you do, trying

to do something different. If I weren't proud of what I was doing, I couldn't

go to a show and stand in front of it."

Contact: Bobby Michelson, Ramwood Furniture, 2127 1st Ave. S., Birmingham, AL 35233. Tel: 205-323-5070. www.bobbymichelson.com